It’s Saturday afternoon and it’s perfect weather for a picnic at Dolores Park. I’m introduced to a mutual friend when they eventually ask, “what do you do for work?” and to this day I have to pause every time.

Two years working at a biotech startup, and even some of my closest friends don’t understand exactly what I do between 8 to 8. So, every time someone asks me that question, I think about how many degrees away they are to the lab bench, and give an answer that’s usually some variation of:

“I work in a biotech startup [in San Francisco] as a biologist, trying to find cures for age-related diseases.”

In this three-part series of my first-ever blog posts, I want to break down that statement and go a little deeper on a few keywords. Today, I want to talk about “biologists.” How they come to be, and what it means to be one.

Picture a Biologist

But first, picture a “Doctor.” What comes to mind? I think we all have a pretty similar image of our pediatrician, Grey’s Anatomy, or maybe even Doctor Mike? (I’m more of JIN or House fan)

Then how about a “Biologist”? What comes to mind? Chances are your image of a Biologist is much more vague.

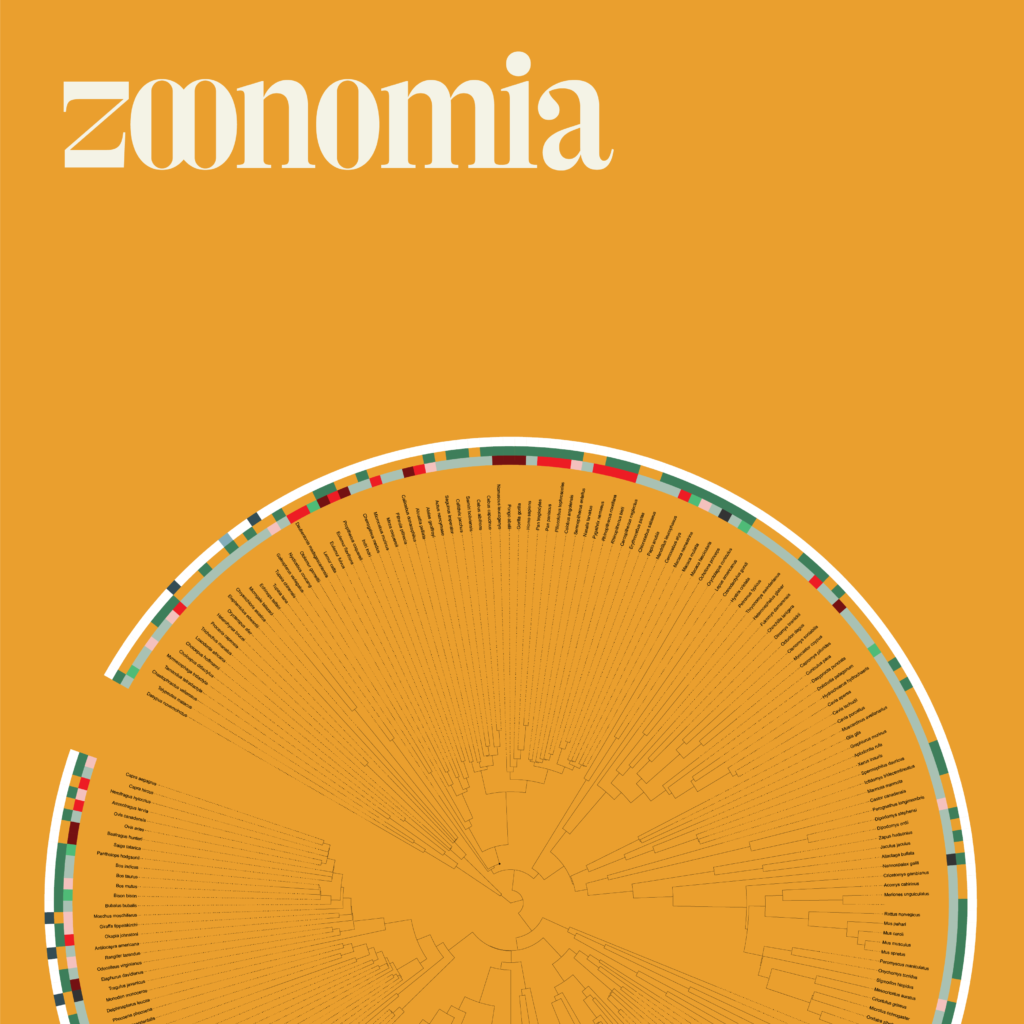

But that’s totally fair, I mean, what do they do anyways? Survey the invasive deer population in Wisconsin? Cell culture experiments in human-derived heart cells? Or analyzing the DNA sequences of a horse, seven squirrels, and a spiny mouse?

They actually do all of that, and a whole lot more. Most of us probably have a clear image of a “doctor” thanks to TV shows and interacting with them all our lives, but most of us don’t really interact with biologists while they’re working. So the general image of a biologist is way more vague, making their lives, journeys, and experiences unique and untransparent to people on the outside. So I wanted to talk about the path to become a biologist. This journey usually spans a decade for most people, with lots of twists and turns. Here, I wanted to describe a relatively straight forward path of a specific kind of biologist: Cancer Biologist.

Step One: Don’t f*** it up

They say the first step’s always the hardest. But the path to a biologist is arguably one of the hardest to start. To become a biologist, you need to join an academic lab first. Let’s say you’ve always been interested in cancer, and after reading The Emperor of all Maladies in high school you were inspired to discover ways to fight cancer that don’t rely on zapping your body with radioactive waves.

You ace AP Biology and enroll in a big public university like University of Michigan. You dream of being a kickass Cancer Biologist and start taking intro-level biology classes in your first year. A few of your classmates are talking about joining an academic lab next year, and after doing decent in your biology classes, you think of doing the same.

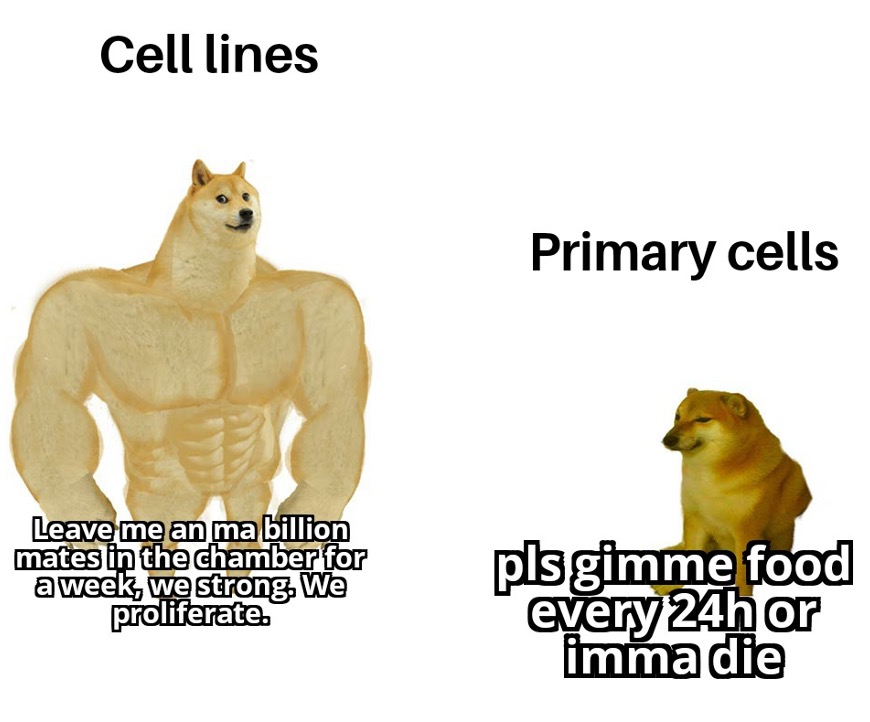

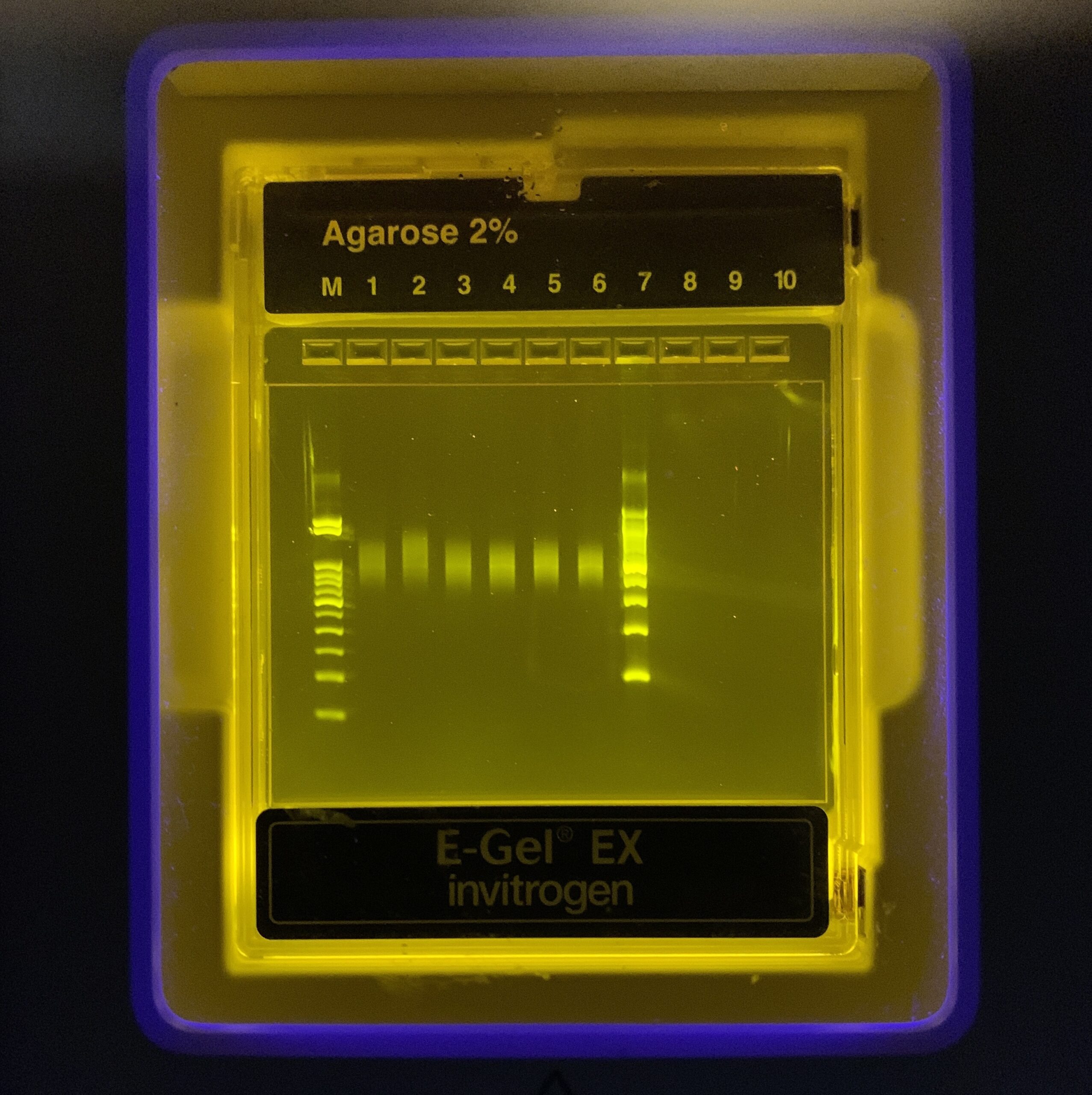

To become a biologist, early lab exposure during your undergraduate years is everything. Your early years in an academic lab look a lot like apprenticeships for trade jobs: lots of hours, minimal pay, and your only job is to not mess it up. Do this gel extraction, retransform this plasmid, change media on these cells. As a newbie in a lab surrounded by multi-thousand-dollar equipment, you’re at best a liability and at worst a money drain.

Training a newbie is hard work. Micro-pipetting is not something you do in your daily life, and transferring <20uL volumes of different viscosities is way more difficult and sensitive than you’d think. Working with RNA? Make sure you spray everything down with RNAse Away and try not to breathe too hard, and definitely don’t sneeze no matter what. Changing media? Better learn aseptic technique before you touch anything in the cell culture hood.

Pipetting small volumes of different viscosities, making master mixes, even following standard manufacturer protocols (this ~10hr protocol for example), are skills that take hundreds of hours to master.

Due to the high skill curve of biology (aka “wet lab”) research, the first ~1yrs of being in an academic lab are often spent learning how to do basic tasks, grunt work like autoclaving (aka washing dishes), and doing weekend work that your graduate student mentor doesn’t want to do.

But after the first year or two, you unofficially earn your stripes. People start trusting you to work more closely on their projects. You start joining their discussions with the grad student and Principal Investigator (PI) to help them figure out how they can test whether x gene is doing x thing in a cell. You might even start having your own mini-project, which can be as simple as creating a new plasmid that no one has made in the lab yet, or a more complicated project like inserting different gene-editing constructs into cancers cells to see which genes affect which cells using enzyme assays.

Although the process is grueling, it’s incredibly rewarding. When you first joined you were a complete newbie who wouldn’t be trusted with a simple PCR. The first one took you one hour to do. But now? It only takes you fifteen minutes. With a few years of training and grinding, you start to see yourself as one of them: the crazy smart, imaginative, thoughtful, and skillful scientists that you’ve always looked up to.

In your final year of undergrad with 2-3yrs of mostly unpaid part-time academic research, you’re finally looking at the next step to become a Cancer Biologist: a PhD.

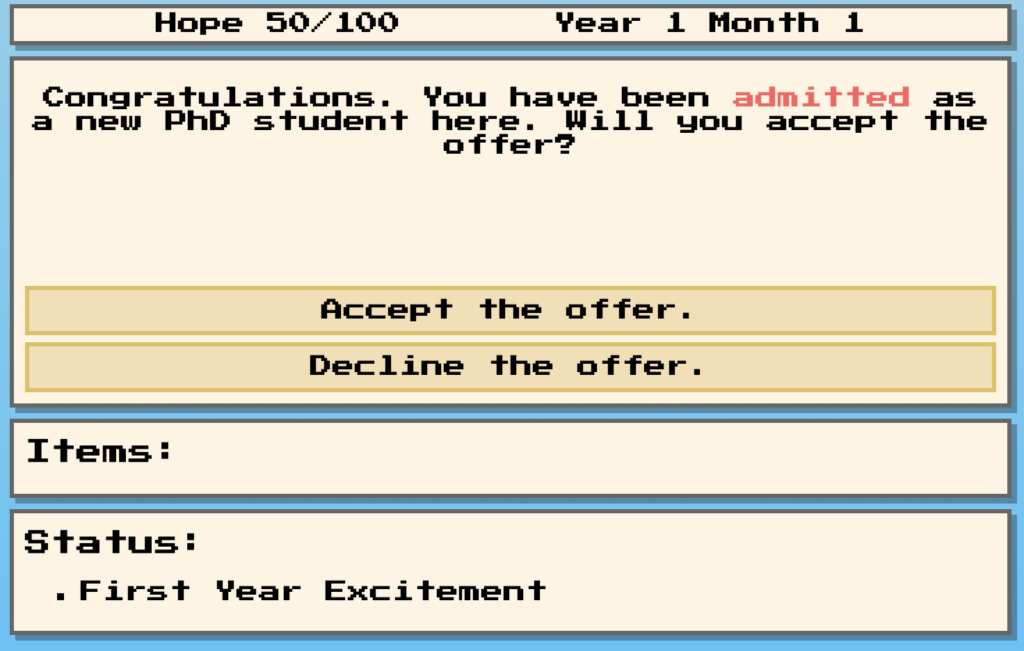

A succinct, extremely accurate, meme-able illustration of a PhD.

Step Two: Keep Pushing

In a PhD, you truly approach the New Frontier. You join a lab with a very specific research area that is shaped by the PI, the professor, who spent a lifetime studying the subject who then started a university lab to continue their research. Their specialty is cancer biology, specifically Chimeric Antigen Receptor (CAR)-T cell therapies, and more specifically engineering CARs with base editors and non-viral vectors to generate them at-scale.

You have no idea what any of that means, so you hit the books. The first ~1yr is spent mostly on reading ferociously to try to understand the current state of the field, where the gaps are, and where you can innovate. In a PhD, you are at the edge of your field and must become an expert in your research area. You read a lot, try lots of experiments, fail a lot, and keep pushing. Over the next four to six years in your PhD, you slowly build a portfolio of ideally three or more papers in a “high impact journal,” threading together a story for what and how you pushed the boundaries of modern science in your studies.

If joining a research lab in undergrad was like starting a trade apprenticeship, earning your PhD is akin to joining the guild. After hundreds of hours reading papers, plenty of failure, months of writing, and years of experimentation, you finally earn the title: PhD. You’ve pushed the limits of modern science and found a new way to manufacture CAR-T cells using a scalable non-viral DNA vector using proteins from eggshells! You are now a Scientist. You observed the world around you, and imagined it differently. It’s been nine years since you first joined that lab as a newbie. Nine years since you tried your first PCR. Since then, you’ve paid with your blood, sweat and tears, and fought in the New Frontier to become the Cancer Biologist you’ve always dreamed of.

Step Three: Find your path

But after a tough PhD experience, you’ve started to doubt whether you should stay in academia. 60hr work weeks are normalized, terrible pay (~$35,000/yr grad stipend), and the culture of independence could feel isolating at times.

After a PhD, there are generally two options for Biologists: Academia or Industry. AKA, become a professor or a Scientist at a biotech company. AKA, stay two more years to try to publish that fourth aim that didn’t make it on your PhD dissertation, or leave it to that first-year grad student to finish it in four.

Through six years of dedication, you carved out your niche and became an expert in your research area. You think of joining a biotech company for the better work life and way better pay, but you’re not sure if you should do it. You’ve never really talked to people in industry, and the idea of staying in the same lab with more freedom to just focus on your research sounds safe and appealing. Besides, your PI seems super excited to have you as a post-doctorate researcher. Plus you might even want to become a professor someday, and to do that you almost definitely need to do a post-doc.

The path after a PhD is much more nuanced, and I won’t go into the details here mostly because I haven’t seen enough of what happens after. Many PhDs would do a post-doc, but that’s becoming less common these days. Since ~2020, there has been a significant decline in post-docs throughout academia. There are many socio-political and economic reasons for this that I’m definitely not qualified to talk about, but here’s a good article about it if you’re curious to know more. But honestly, who can blame them? Considering the salary alone (~$60,000 pre-tax for a post-doc position, even at Harvard), being ~30yrs old after four years of undergrad and six years for the PhD makes that kind of salary unfair and unlivable, especially if you want to have kids soon.

That’s why many PhDs have been moving to industry. To a biotech or pharma company, a bigger city with a better salary and a collaborative environment, applying your research to something that has a stronger potential for direct patient impact in the near-term future.

But life as an academic can still be extremely rewarding. You have near-complete control of your research and can work on your own schedule with few fiscal or investor expectations. But it’s also a life that demands a lot from you, and there’s a reason why you don’t see too many of them out at the bars on a Friday night. Unless you were in an academic lab yourself, it’s hard to understand the life of a PhD.

So I hope this post shed some light on what it takes to be a biologist, who they really are, and why they do what they do. Maybe next time you meet a graduate student at a bar, you’ll have a great conversation with them because you’ll understand a bit more about what they’re going through. And similarly, if you meet an attractive 30yr old “post-doc at Stanford,” you’ll remember that he probably makes less than you. So buy him that drink.

Final thoughts

There are no “Biologists”, just “Scientists” and “Researchers” that are experts in a very specific subject who’ve spent over a decade studying and polishing their skillset. Even the “Cancer Biologist” is not really accurate, she’s more of a “CAR-T cell Scienitst.” Just like how you can’t take your Plummer to your house’s electrical circuit, you can’t take a Cancer Biologist to Bluffview, Wisconsin and have them survey the invasive deer population.

And yet, many of us go by it because it’s often way easier to say. Because when I introduce myself as a “Gene Therapy scientist specializing in AAV delivery, in vivo disease models, molecular biology and single cell sequencing”, I often lose people at the first word. But next time if you meet a Scientist or Biologist, ask them what specifically they do, and keep asking questions. Because they’ll love to talk about their research outside of meetings with their PIs when they’re getting grilled on the spot.

Most of us Scientists are therefore academics at first. We often have PhDs and/or have spent at least six years of our adult life in a lab, pipetting and working twelve-hour days for weeks to get our experiments to work. We’re experts who can operate >$500,000 machines of the future on just three hours of sleep. But we’re also the ones bound by cells on a petri dish that can die at anytime for, like, no reason.

We observe the world around us and imagine it differently. Using every single tool available, we pore over journals to find a technique that just might prove that our theories to be true. It’s an endless cycle of ideas, experimentation, failure, and success. We thrive in it. And while many of us imagine a life someday of never having to touch a pipette again, we take pride in our technique and executing our experiments with our own hands every single day.

I hope this gave you some insight as to what “Biologists” are and what we do, what it took to be one, and what this “job” means to us.

*Disclaimer – I don’t have a PhD. I just spent my entire adult life working for/with them.

Leave a Reply